Born in the mutinous middle of the twentieth century in 1953 I have been writing for over forty years now, which I guess adds up to a wilderness. What fun it’s been despite the poverty. And as for recognition, can we ever have enough? Social media hopes the answer is no and has got rich on the punters spinning the wheel. My pay off lies elsewhere and has been considerable, placing the words on the page, cradling them in their nether world so that one day they can meet their readers and live independent lives.

Life began in Fort Street Petersham in Sydney, Australia. It was a working class suburb then; full of gracious houses reimagined as decaying hostels with rigging out the back, washing lines full of holey singlets and clothes that survived the steaming copper and ringer. As I remember it the first pages I ever saw were the flattened squares of handkerchiefs and other items that emerged from the rollers of the suburban printing press.

We moved to Haberfield which at the time was considered an upgrade. I started school with the Presentation nuns at Five Dock, and you’ll have to read ‘Promise of Rain’ if you want the grisly details. Secondary school was a further upgrade to the Dominican nuns at Strathfield. I made good friends and discovered that I could sing baritone under the main hall while examinations were being conducted. My love of musicals has continued.

Sydney University was followed by three years in Alice Springs, then several years in London, France and New Guinea. I met many people: I would sit at the Union Refectory at Sydney University with Malcolm Turnbull, Kathy Fulton, David Marr and Stephen Neall. I went to a poetry group where Dorothy Porter presided. I met Clive James, AD Hope in London, the ageing Countess Korolyi in the south of France, Prince Charles in Alice Springs. I was taken to the Groucho Club. When I returned to Australia I formed close friendships with Geraldine Brooks, Richard Glover, Debra Oswald and many more. I was in no way deprived of good company. But as time moves on there are two trifling tics which remain on my carcase and refuse to drop. The first is the naked Swede that wandered the jungles of New Guinea with a briefcase under his arm. The second was the Australian artist, Sam Atyeo, whom I met in Nice all those years ago. He was growing roses to supplement his income while bemoaning his lack of recognition in Australia. Sam had displayed an early commitment to cubism which had become doctrinaire in the south of France. He lived to proselytise the virtues of abstraction. He gave me a piece of advice which I treasure, but which was probably meant for himself. ‘You have to remember this: as an artist you have to keep your refrigerator full.’ He had had to leave his country, fight for his abstractions, keep on painting, and instruct youngsters like myself not to give up when things got difficult and the granary stores were under threat.

Four novels later, I adopted seven year old twin girls from Sri Lanka at the age of 37 (sadly, at the same age their mother died four years earlier}. This has been a challenge and a privilege. A mid-life grenade that when stepped on completely transformed the artist’s idyll. The marriage limped along for seven years, and after twenty four years ended in divorce. It was a time of reckoning. I was now working full time and writing in secret fleeting moments. My lover was not the nubile young thing, but the ancient tradition of words coaxed out of their hidey holes and onto reluctant pages. I still managed, don’t ask me how, to write a musical, which thanks to the input of the talented people of Kiama and the Illawarra eventually made its way to New York, to the very same theatre Fanny Brice (the subject of Funny Girl with Barbra Streisand) had performed. The big lesson for me as a result of this time, just before the twin towers came down, in August 2001 was the value of collaboration, the sheer wonder of not having to work alone. It also gave me a real intimation of the power of tradition. We are not alone and are indebted for every feather that allows our work to take flight.

The international environment was about to change. It was August 2001. I returned to Australia in a blizzard of confusion, with a loss of faith that civilisation, or my part in it at least, could be restored. European culture had lost faith in itself and wave upon wave of post modernism would bathe its wounds with inane consolations.

These were the years of exile, hard work and writing books that no one seemed to want. Celebrity was the foundation for the new order of things. Attention spans were the length of a kitten slap and a new barbarism emerged as people fought for prime time. If we had lost most wars since 1945 then we would have to take the fight to a virtual space. I’m not sure it’s working for we are quite literal creatures. Let’s hope we can find virtue in the virtual.

In the last fifteen years I have collected a number of books which remain unpublished. The most recent of these is an e book. ‘Songs from the Iron Age: A Story of David’ I am currently in the final stages of writing a novel about the eighteenth century which features Friedrich of Prussia, Voltaire and Maria Teresa

the Habsburg ruler. It is wondrous to enter another world and inhabit it like a monstrous dullard, a dolt, picking up any stray pieces of wisdom that fall from the table. If we don’t live respectfully in the shadow of others we are doomed to become shadows ourselves. And on that note I invite you into my world.

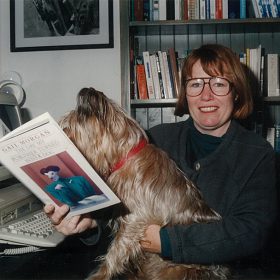

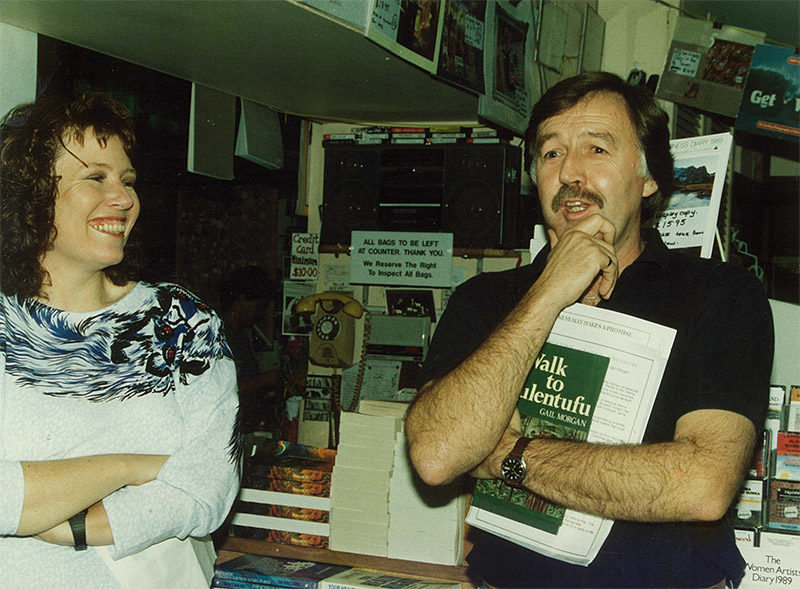

Gail Morgan